Reiji Suzuki

Professor, Ph.D. in Area Studies

- suzuki.reiji

- Areas of Research

- Forest Environmental Science, Soil Science, Area Informatics

- Profile

- Research

-

Dr. Reiji Suzuki is from Kita-Kyushu City, which is located in the northern Kyushu Region. At university, he studied in the Department of Agricultural Chemistry of the Faculty of Agriculture at Kyoto University and majored in Forest Soil Science during his fourth year. He then went on to graduate school at the same institution, where he joined a project involved in environmental research around the Kazakh Aral Sea. At that time, the area was facing a serious environmental problem caused by soil salinization, and Dr. Suzuki worked to understand the mechanism and consider countermeasures for it. It was around this time that his interest in environmental problems heightened, and he began to feel a hyper-awareness of these problems taking root within himself.

After earning his master’s degree, he worked for a private environmental consultancy for five years, where he was in charge of research and planning measures related to environmental assessment in Japan. In many ways, he had a valuable experience that led to improvements in his management skills and field research skills. After that, he returned to Kyoto University and completed his Ph.D. in Area Studies at the Graduate School of Asian and African Area Studies (ASAFAS). Up until now, he has been conducting field research in Japan and Southeast Asia. As a professor of the Department of Bioenvironmental Design, he is in charge of Specialized Course(s), which includes Environmental Biology, SATOYAMA Studies, and Forest Stand and Soil Science.

Dr. Suzuki belonged to the mountain club in high school. The beautiful view of the Northern Japanese Alps he visited in those days remains etched in his eyes. He still enjoys the outdoors on his days off and partakes in climbing, hiking, and camping. -

An old-growth forest deep in the mountains and a man-made woodland near the human living sphere. Which is inhabited by more diverse creatures? Many would choose the old-growth forest, but in fact, nature, such as satoyama (area between plains and mountains which is located near human settlements and has been used by people for their daily lives), where people continue to collect firewood and charcoal and rake leaves for compost, is home to as many creatures as old-growth forests.

In old-growth forests, trees and flowers grow under thick branches and prefer dark places, but satoyama is the opposite. For example, sawthorn oak and chestnut-leaved oak and the rhinoceros beetles and stag beetles that gather in their sap, as well as the liliaceous plant Japanese dog’s tooth violet and the nectar-sucking Japanese luehdorfia, which can only grow on the surface of bright forests in early spring, prefer a satoyama-like environment over old-growth forests. Satoyama has created an ecosystem in which human activities are also a component, and a variety of living things have lived in a sustained coexistence between humans and nature.

However, in Japan today, fuelwood and compost are no longer used in daily life, and many satoyama have been abandoned, transforming into transforming into forests with dark forest floors.

As a result, suitable habitats for many species that prefer bright environments have declined, and many species are threatened with extinction. In Kameoka, where the Faculty of Bioenvironmental Sciences is located, there are still satoyama consisting of sun trees such as chestnut-leaved oak and sawthorn oak. However, saplings of these trees are not growing on the forest floor, which is becoming dark due to poor management, and there is a shortage of successor trees. Even in the world of satoyama, declining birthrate and aging population are progressing. As people’s lives change and the environment of satoyama changes, how can the lives of these organisms be sustained?

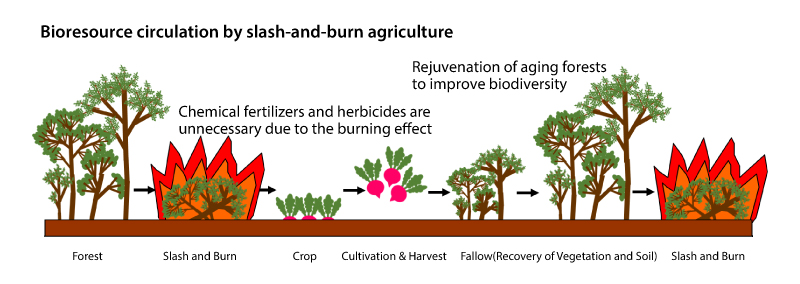

With this in mind, Dr. Suzuki has focused on the traditional farming method known as “slash-and-burn farming”. Some associate slash-and-burn farming with deforestation, but it is actually a cyclical farming method that takes advantage of nature’s regenerative power. It is based on the premise of “returning to the forest”. If the land is allowed to rest after one or several years of growing crops, vegetation will naturally recover in warm and humid climatic conditions, from grass, to brush, to the forests. A virtuous cycle is created in which once burning a forest in a neglected and densely vegetated satoyama promotes its rejuvenation and helps produce crops in hilly and mountainous areas where cultivation has been abandoned.

Others worry about the impact of burning trees on global warming. The logic that burning increases carbon dioxide in the atmosphere is also a misconception. The fuel used in slash-and-burn is the biomass stored inside plants. Unlike the burning of fossil fuels, the total amount of carbon dioxide has not increased because plants only take it from the atmosphere through photosynthesis, and the carbon dioxide that had accumulated in the body as a carbon compound is returned to the atmosphere by burning.

In addition, when a field is burned, ash from plants and trees becomes a nutrient, and nitrogen in the soil becomes easily absorbed by plants, so the soil becomes rich without the need for additional fertilizer. The seeds of weeds in the soil also lose their germination ability from the heat of the burning, so there is no need to spray herbicides. Although slash-and-burn farming in Japan declined after the 1950s, in recent years it has gained attention as an organic farming method that does not require herbicides or chemical fertilizers. And since around the 2000s, there has been a nationwide movement to revive slash-and-burn farming.

Dr. Suzuki’s laboratory is also engaged in slash-and-burn farming in a deserted satoyama in Yogo Town, Shiga Prefecture, where they grow “Yamakabura”, a local traditional red turnip. Many students take part in burning and harvesting each year, and some choose slash-and-burn as a theme for their graduation research studies. They apply the knowledge acquired in lectures to field practice through trial and error and take initiative in conducting research on themes they have set for themselves, such as vegetation recovery after burning, the effects of fertilizer application in burning, and the quality evaluation of turnips.

It has long been said that red turnips from burning fields are chewy and brightly colored. Dr. Suzuki’s laboratory is developing practical research activities that will lead to regional development by growing wild turnips as regional brand vegetables while regenerating the satoyama.